Living in a Sexualised Society

written by Anna Webster ©

Introduction: The Effects on Young Girls

I have recently found myself contemplating how my upbringing and the way I see myself today would possibly be different if I was born in the year 2000 rather than in 1993. I look at young girls now who are barely entering their teenage years and wonder how it appears that so much has changed since I was at the age of twelve, wearing clothes that my mum had bought for me and no make-up. My cousin is now at the age of twelve where wearing the latest fashion labels, hair extensions and false nails is a big part in constructing her image. Although to my family we look so alike, I have found that being seven years apart we could not be more different. I feel that living in a sexualised society plays a major role in influencing young girls to convey a certain sexual maturity and portray an image far beyond their years. Adult sexual motifs are seeping into products and clothing targeted at children so much so that it appears the gap between what is produced for children and for adults is being pulled closer and closer together. Not only is the merchandise aimed at young girls pushing the boundaries of “sexiness”, but the images of women we see in our day-to-day lives, in particular through advertising and music videos, emote a certain provocative and sexual allure that can in turn have many harmful physical and mental effects on young girls.

This is an issue which I feel personally close to and which I believe has enhanced since I started the course in October. My evolving sociological imagination has allowed me to acknowledge this issue by recognising the influence of the wider structures of society, in conjunction with how individual biographies are situated within this wider framework and how this may change over a period of time (Wright Mills, 1959). In particular how the impact of the media industries‟ portrayal of women influences many young girls today. In contrast to the time when I was at a young age, I find that there is a certain pressure applied on children to conform to a sexualised image. I am going to elaborate on these issues by adapting the ideas and theories of Gramsci and Marcuse to my chosen topic in terms of the impact of the media affecting consumption at a macro level of analysis. I will also adapt the works of micro-level theorists Mead and Goffman who explore the meanings and understandings established through interaction in relation to individual action.

A Culture of ‘Hotness’

When I pick up my favourite glossy magazine such as “Look” and “Cosmopolitan” or turn on the television it appears that in today’s image – orientated culture the women staring back at me are presented, positioned and poised in increasingly sexualised ways. I feel that as a society we have been thrust into a world in which the seductive images we see everyday teach us that desirability and attraction are the most important accolades you can achieve. Young girls in particular are becoming increasingly influenced by the fashion, music and advertising industries that advertise that “they should look “hot” not later but now” (Reist, 2008: 42). As a result, they are growing up alongside sexually saturated images in a society which is preoccupied with being evaluated on terms of sexual appeal. Looking at my cousin who does not need to wear make-up or designer fashion labels to make herself look more attractive, I can see firsthand how young girls in today’s narcissistic and consumerist society feel they need to aspire to create an older and sexualised image of themselves (Reist, 2008). For example my cousin regularly straightens her hair, wears false nails and eyelashes, all of which are common rituals associated with adult behaviour and are now making their way into childhood as a result of the sexualised images they see every day.

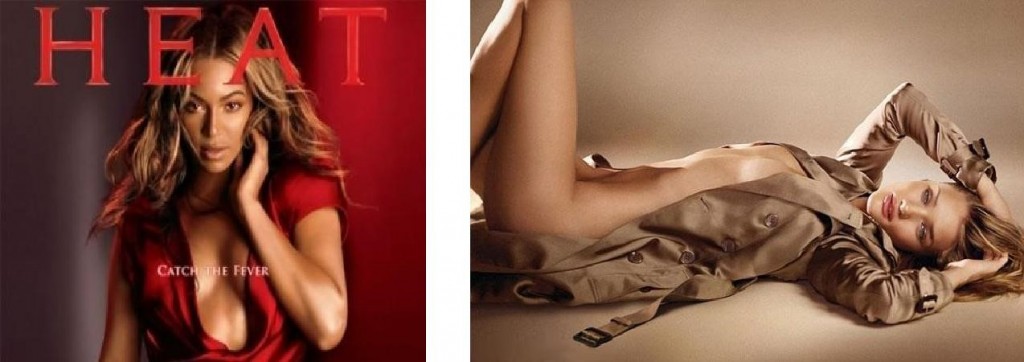

I feel that the impact of advertising plays a significant role in this, as it has been argued that children subjected to advertising desire many of the intangible values associated with certain products, in particular sex appeal (Fox 1996, cited in Strasburger and Wilson, 2002). In many ways, it has become a natural occurrence for adverts to feature thin, attractive models in provocative and visually exciting scenarios. Although this is a common marketing strategy to influence consumers, studies have found that young girls in fact compare their physical attractiveness to models featured in advertising, which in turn can have many serious effects (Martin and Kennedy 1993, cited in Strasburger and Wilson, 2002:62). An area of the media which I feel particularly highlights this concern is that of perfume advertisements. Icons such as Beyonce have recently been criticised for overly explicit content in the advert for her new fragrance “Heat” (see image 1). It features the star dancing seductively with the camera showing her chest and thighs as she caresses her neck and breasts (Poulter, 2010).

I have found that many other brands have used half-naked celebrity icons to endorse their products in order to make the brand more seductive and sexual. The stunning actress Rosie Huntingdon-Whiteley has recently become the new face of Burberry fragrances, in which she appears dressed in nothing but a trench coat, positioned in a sexually inviting pose, running her fingers through her hair and staring seductively down the lens of the camera (see image 2). I feel that it is examples like these used in the advertising world, which filter what young girls view as “perfect” (Wright, 2011: 3). It is extremely rare for an unattractive and overweight model to appear in such campaigns. These depictions of women in the media industry emphasise how women should look in overtly sexual ways, and as a result it becomes increasingly difficult for young girls to pull away from this notion. It is as if they have become so entangled in a web where a perfect sexual image of females has become the norm, that they are effectively trained about how to present a hypersexualised version of themselves (Reist, 2008: 10).

Music Videos

It has been argued that various Pop and R’n’B style music has always been somewhat sexually inclined; however, in recent years it has become even more obscene and in some cases has descended into pornography (Wright, 2011: 70). In one recent analysis of popular music videos, researchers found that in 84% of the videos analysed, women were shown to be dancing in a provocative nature (Ward and Rivadeneyra, 2002 cited in Walter, 2010: 33). It is clear by watching various music channels that the female artists whom young girls are encouraged to look up to rely heavily on their sexiness, raunchy costumes and suggestive dance routines (Walter, 2010: 35) to attract attention and most importantly to sell records. The display of sexualised women as objects of desire has become a crucial element to the industries’ economy in achieving both pleasure for the audience and profit for the companies (Rauton and Watson, 2005: 115).

I want to explore the differences which the music industry produces between male and female characters in various music videos. I have taken the example of “Ayo Technology” by 50 Cent and Justin Timberlake to highlight this. In the video both artists are fully clothed in suits in comparison to the array of female strippers who appear in extremely sexualised clothing and in some cases just their underwear (50 Cent ft. Justin Timberlake-Ayo Technology, 2010). In one scene Justin Timberlake is watching a woman in her bedroom as she undresses down to a bra, hotpants and stockings (50 Cent ft. Justin Timberlake-Ayo Technology, 2010). Further into the video in a room full of semi-naked women, 50 Cent enters while the women dance erotically for him; he is blindfolded while a lap dance is being performed in between his legs (50 Cent ft. Justin Timberlake-Ayo Technology, 2010).

Throughout the video, the representation of women conforms to a very pornographic version of sexuality that involves stripping and sexual servitude to men (Durham, 2009). In this case “sex is displayed as something purely physical based on female exhibitionism” (Durham, 2009: 73). There are no explorations of mutual love or respect, the woman’s role in this video is purely to excite the male gaze (Durham, 2009: 54). It is very rare for women in these videos to be presented as the “gazers” of men – their sexuality never translates as anything other than a form of sexual and desirable stimulus (Durham, 2009: 54). I also feel that the choice of lyrics used in this particular video suggests that men should stay passive in sexual encounters while women should be sexually available to attend to their needs “She always ready, when you want it she want it…if you want a good time, she gone give you what you want” (www.metrolyrics.com/ayo-technology-lyrics-50-cent.html). The current enquiry into music videos receiving a specific age rating has been sparked by the increasingly sexualised nature of many music videos such as this, shown before the nine o’clock watershed (Harrison, 2011). However, I believe that in today’s contemporary and digital society, new media has become increasingly individualised. Young adolescents can now view these videos via the internet on sites such as “YouTube” or through the interactive services on many household televisions.

They are becoming more and more accessible to young viewers despite media regulations and are coaching young girls to project a very adult sexuality (Durham, 2009: 62), which is subservient to the male gaze.

Antonio Gramsci

Having looked at the examples of advertising and music videos as areas which contain strong sexual presentations of women, I believe that this constant exposure to such images can create a distortion between reality and a fabricated, media-constructed version of the female image. The vast array of airbrushed images claiming that super slim women have the “perfect beach bod” have become splashed across the pages of teen magazines, consequently leading its young readers to believe that there is no other image worth aspiring to (Brooks, 2008). Many are under the assumption that as individuals we have a free choice in accepting as truth or not the images we see, yet I feel that in the modern world they are inescapable. Not only do we see increasingly sexualised depictions of women in the confines of our home, but to a certain extent the public sphere has been hijacked by these images too (McGuigan 1996, cited in Rossi, 2005: 129). If it is not the visual tricks the media play on innocent minds, many body-critiquing messages from shows such as “Extreme Makeover” and “America’s Next Top Model” become internalised by young girls (Reist, 2008: 18), messages that particularly value girls who are “hot, thin and sexy” (Reist, 2008: 8). Girls see women in the media spotlight subjected to constant scrutiny, creating anxiety for their own self-image. This anxiety, however, is beneficial for businesses, as it keeps girls purchasing (Hamilton, 2008: 44).

Such ideas can be related to Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, which suggests that the dominant and cultural ideologies in society are secured by the most dominant groups in order to maintain a coercive position (Strinati, 1995: 148). It has been argued that because young girls have limited life experiences, they do not question the sexual images they see (Hamilton, 2008: 44). Marketers use hypersexualised images because “sex sells” and as a result the more sexualised the material we see, the more desensitised we become to it (Hamilton, 2008: 45). Gramsci argues that as a result we tend to assume that is the way things are meant to be, as we naturally think along the lines already organised for us (Inglis, 1990: 163). Consequently, it can be argued that this constant subjection and pressure to live up to a culturally designed appearance ensures that young girls believe that this image is the most dominant and pervasive (Durham, 2009: 65). However, I feel that it is extremely important for young girls to be aware that the majority of images they come into contact with are in many cases airbrushed, exaggerated and eroticised versions of women (Durham, 2009: 65). This is because the more images of sexualised images girls see of so-called “perfect” women, the more they believe this to be what every woman should look like. It is very unlikely that we should come across plus-sized models, those who are a size 16 plus, sexually posing in perfume campaigns and on the covers of magazines. Much emphasis is placed on the sexual appeal of these women and how they serve as compelling role models, yet young girls should be taught to acknowledge they are in fact effigies of what a modern society has depicted as perfect (Durham, 2009: 67). In fact, many of the images we see are a far cry from the real world (Durham, 2009: 67).

‘Mini Me’ Culture

Walking through the town centre today we see that many of the shops we recognise for selling adult clothing now include a range of clothes for children. When looking at many of the designs it is likely that the average person would assume that they are aimed at their elders. One example that I found most shocking is in “River Island”, a shop intended for late teen and adult-wear, which has now included a “boys and girls” section. From leopard print skinny jeans to lace ra-ra skirts (see images 3 and 4 previously) these sexy items start at sizes aged 3-4 years old (www.riverisland.com.online/girls, 2012). However, what I find most disturbing is that these items along with many other examples are also sold in the women’s section, but in bigger sizes (www.riverisland.com/online/girls, 2012). It is evident that many brands of clothing sold to young girls allow them to buy into this sexualised culture, which pays much attention to obtaining an older image (Walter, 2010: 35). The fashion industry has created an “adultification” of products (Edwards, 2011: 88), which allows barely teenage girls to dress as adults; it is now possible for these girls to dress in exactly the same clothes as their mothers. I remember as a young child trying on my mum’s dresses and high heels, using her lipstick and hanging her jewellery around my neck. To me, pretending to be an adult just for a few hours before your mum finds you and wipes the make-up off your face is a very normal part of growing up. Yet in today’s modern and ever-changing society it takes very little imagination to enter the world of role play and “make-believe” and many of these products are produced with children in mind (Brooks, 2008: 92). We have reached a point where dressing up in this way in the private domain is acceptable, yet as soon as young girls take up this image in the public domain, it is seen as a cause for concern (Brooks, 2008: 92).

Image 3: River Island, Girls Pink Image 4: River Island, Girls Cream

Leopard Print Skinny Jeans, 2012. Lace Ra-Ra Skirt, 2012.

However, it is not just the available clothing which is luring kids out of their childhood faster than ever (Brooks, 2008: 93), but also the underwear that is worn underneath it. ‟Abercrombie and Fitch’s thong underwear for pre-teens and La Senza push-up bras in sizes for little girls bring up much of the same problematic and sexualised associations” (Durham, 2009: 83). Much controversy has been caused about the shop “Matalan‟, which sparked outrage among many parents for selling “a range of padded bras available in sizes as small as 28AA” (Daily Mail Reporter, 2011) (See Image 5). Disagreement has been caused regarding this, meaning that stores such as “Matalan‟ and “Primark‟ need to stop products that “treat girls like women” (Shipman, 2011), as “first bras should be constructed by the industry to provide comfort, modesty and support without enhancement” (Shipman, 2011). Not only are many of the bras targeted at young girls promoting breasts to look fuller and more enhanced, but some of the slogans printed on them are sexually suggestive in their message (Shipman, 2011).

Products include High School Musical themed underwear with the slogan “Dive In” as well as bras that have “Little Miss Naughty” (see Image 6) across the breast area (Shipman, 2011). Retailers and producers of these items are slowly pushing the levels of acceptability further and further to encourage children to act in a manner beyond their pre-teen years. One of the reasons behind this over-sexualisation of clothing and underwear aimed to be worn by young children could potentially be that such businesses have begun to work in conjunction with the highly-sexed presentations in the media. Designers of pre-teen underwear now recognise that these are the type of items most favourable to young girls in today‟s society and as a result have the ability to create cheap high-street versions, which makes this „adult image‟ even more accessible.

Image 5: Matalan, Heart Image 6: Daily Mail, Little

Image 5: Matalan, Heart Image 6: Daily Mail, Little

Bra Peach, 2010. Miss Naughty Underwear, 2011.

Erving Goffman

The theories of Erving Goffman are a microanalysis of interaction and are concerned with what people do when they are in the company of others (Williams, 1980: 190). Goffman recognised that through interactions stable patterns arise, common rules and actions, common knowledge, in which we recognise a range of social actions (Williams, 1980: 190). I feel that this notion can apply to forms of clothing in the sense that through interactions clothes can create specific social codes (Durham, 2009: 81). We create common rules and values about certain styles which we believe to be the norm for different groups. In today’s society you can now tell a lot about someone from the way they dress, “they convey attitudes, qualifications, social awareness, class rank or status” (Durham, 2009: 81). This may provide one explanation for why many young girls believe that specific styles of clothing help them to find acceptance within a group (Durham, 2009: 82).

I have been told by my cousin that at her secondary school wearing popular brands such as Hollister, Jack Wills and Paul’s Boutique are essential if you want to be part of the so-called “popular group.‟ She went on to explain how if you do not wear these branded items you will be laughed at or teased by the rest of the group. I find this to be a huge contrast to when I was at secondary school, having a big group of friends where what we wore played no part in “gaining acceptance” – if anything individuality and different styles of clothing was embraced rather than rejected. Yet now these specific brands which promote older, sexier styles of dress create an environment, in which young girls begin to evaluate each other, dependent on their clothing. This analysis ties into Goffman’s theory of the self as a social product in the sense that individuals put on different performances depending on the social situation (Lemert and Brananman, 1997: 23). In relation to clothing, our different social codes include appropriate attire for different contexts (Durham, 2009: 82). For example I have seen that when my cousin goes out with her friends into the public domain, she will wear clothes that are deemed desirable by the „school culture‟, however, when she is at home, she will dress down in more casual clothing that is appropriate in the private sector in front of her family. Goffman acknowledges that enhancing our own self-image in the eyes of others is the most essential way we commit ourselves to the dominant ideas of society (Lemert and Branaman, 1977: 21). Therefore, as more and more sexualised clothing becomes available to young children, the pressure to conform to this style increases. Yet the questions remain – are girls dressing up for male attention? For each other? Or to uphold their image in society? (Durham, 2009: 24). I personally feel that this is a hugely important issue which needs to be further investigated and researched in order to target the main sources which enhance this widespread sexualised belief in image and appearance.

‘Girls with a Passion for Fashion’

Not only has increased sexualised clothing become produced and available to younger and younger girls, but also much disagreement has been created based on sexualised merchandise and products which target young children. Of particular concern are “Bratz Dolls” – “mini-skirted mannequins, which outsell more conservatively dressed Barbie dolls by two to one” (MacRae and Sears, 2007), with many girls suggesting that Barbies have become “boring” and don‟t have “attitude” like Bratz (Brooks, 2008: 96). The brand‟s slogan “Girls with a passion for fashion” was created by manufacturers “to persuade us that their sexualised style of clothing is the height of fashion and that young girls should be wearing the same” (Durham, 2009: 74). However, it has been argued that much of the clothing which includes extremely short skirts, high heels, knee- high boots and stockings (Brooks, 2008: 96) (See Image 7) is an attire suitable for a “gentlemen‟s clubs and pole dancing” (Durham, 2009: 83). It is these associations with sex work which are most worrying, as these dolls aimed at a demographic between 7 and 13 encourage the belief that these are acceptable forms of dress (Brooks, 2008: 96). Their general appearance too can be regarded as overly sexualised as the dolls themselves are branded only as „girls‟ themselves. Unlike the classic Barbie (See Image 8), their eyes are bigger, layered with eye-shadow and liner, highlights in their hair and pouting rouge-coloured lips (Brooks, 2008: 96). To me this is more like a depiction of an older woman before a night out, not a girl in her everyday clothes.

In order to reinforce and establish the Bratz brand, merchandisers have also created DVDs, electronic games in which the girls travel overseas, date, become rock stars and hang out in night-clubs (Brooks, 2008: 98). A creation of the „good life‟ full of fun, friends and fashion is established by the brand, yet many of the DVDs show that these girls are in the eighth grade, so would only be fourteen years old (Brooks, 2008: 98). Therefore, half of the activities shown in these games and programmes would not even be possible to do for a girl at this age. The brand has created these plastic girls who can practically wear and do what they please; it is a far cry from the real world, yet young girls are being encouraged to believe that this is what they should be doing too. Many retailers, however, including stores such as WHSmiths and Tesco, are now selling a variety of Bratz items such as clothing, underwear, make-up, stationary, linen and furniture (Brooks, 2008: 100). It seems that with all these branded accessories children really can become their own version of “the living doll” (Brooks, 2008: 100). Sexualised products have now overtaken the shelves which were once lined with innocent childhood characters such as Winnie the Pooh, Bagpuss and the Magic Roundabout.

Herbert Marcuse

It is evident from the examples I have given that much of the clothing and products now available encourage young girls to act older at a younger age (Durham, 2009: 47). Marketers deliberately sell these items with powerful sexual overtones (Durham, 2009: 47), knowing they have the ability to “poke the bruises of stigma and stroke the egos of kids desperate to fit in” (Brooks, 2008: 90). In particular, the advertising of such products often conveys the idea that the “product will bring fun and happiness into a young person’s life” (Strausburger and Wilson, 2002: 53). In relation to this notion, Herbert Marcuse theorised that the material items which surround us “can be a way in which the patterns of lives are shaped by society” (Dant, 2003: 70). As the standard of living rises, so does the process of consumption of commodities (Dant, 2003) in which individuals‟ identities become shaped by the items they purchase (Dant, 2003).

Marcuse argued that this link is a result of advertising and articles that continually encourage us what to buy (Dant, 2003). He believes this creates a “one- dimensional society” by which society introjects its needs into the individual (Dant, 2003). However, according to Marcuse, these needs superimposed upon the individual are “false” (Marcuse, 1964) and work to deny and suppress true or real needs, such as being creative, independent, etc (Strinati, 2004: 154). Marcuse saw that these needs are determined by the external powers over which the individual has no control. No matter how much they are reproduced and fortified to become the individuals’ own, no matter how much the latter identify with them, “they continue to be what they were from the beginning – products of a society whose dominant interest demands repression” (Marcuse, 1964: 5). To an extent in today‟s modern world the mechanisms of mass media have largely taken over the roles of other institutions in the process of socialisation, “mediating between the individual and their society.” (Dant, 2003: 71). It seems that we no longer need to sit children down to talk about society‟s norms and values, the media has now filled that void by injecting sexualised messages into children at a very young age. However, these messages are ones which recognise sexual appeal and desirability as a key value in the modern world.

The Effects- Increased Body Dissatisfaction

I have given some examples which I feel are areas in society which have become dramatically sexualised in comparison to when I was growing up. These examples have tried to show how the sexualisation of children occurs when “the slowly developing sexuality of children is moulded into stereotypical forms of adult sexuality” (Rush, 2006: 41). However, I also feel that it is extremely important to acknowledge the risks which accompany this issue.

Many of the images young girls are exposed to through advertising and music videos create an increased desire for a thinner, “ideal” body (Rush, 2006). Girls become more aware of dieting to lose weight and in some cases this may lead them to engage in disordered eating habits (Rush, 2006). Our society has placed so much emphasis on the “perfect body” it becomes increasingly difficult for young girls to accept this as anything other than the truth. I feel that the majority of women we see in the media on a daily basis are displayed to the viewer as having impossibly perfect bodies, which puts great pressure on young girls to conform. For many of these girls the “thin-look has become the normative” (Field et al, 1999 cited in Strausburger and Wilson, 2002: 262). Studies have even found that girls who aspire to look like these women are twice as likely to be concerned about their weight (Field et al, 1999 cited in Strausburger and Wilson, 2002).

In particular, acquiring a “Barbie body” is said to be a “perfect” look which many girls aspire to look like. When I asked my cousin who her role model is she answered Cheryl Cole – one of many of the women in the media spotlight who are examples of “living Barbies” (Durham, 2009: 97). Although this seems to be a look young girls are determined to achieve, when the Barbie doll measurements are translated into human scale “she would be five foot nine inches, have an eighteen inch waist, thirty six inch breast and thirty three inch hips and would weight one hundred and ten pounds” (Durham, 2009: 96). However, according to medical analysis that is “pretty much unattainable without borderline starvation and plastic surgery (Durham, 2009: 97) and would be too skinny to menstruate (Durham, 2009). It is clear that the media, fashion and marketing industries‟ main aim is to achieve profit by choosing to glorify the most unrealistic body type possible, despite the fact that this encourages innocent and naive young children to regard this as an ideal image to strive towards. However, I believe that many of these industries are in fact aware that much of the items they promote are inappropriate for the age range they target, yet unfortunately many still respond solely to the idea that sex sells.

George Herbert Mead

Mead‟s theory of the self focuses on how “each individual’s socialisation structures the mind and the self in two important ways” (Baldwin, 1986: 112). The first is the “common traits that are shared with others and the second, unique personal traits distinct from others” (Baldwin, 1986: 112). Mead argued that this distinction of the self is divided into two separate components, the “I” and the “Me” (Baldwin, 1986). The “I” is the inner self that acts, whereas the “Me” is the outer self we observe from other peoples’ perspective. He believed that the “Me” allows us to put ourselves in the role of the other in order to establish our own feelings about the ways we ought to be in varying circumstances (Baldwin, 1986). “The individual sees himself from the point of view of other individuals which form the point of view of himself”(Mead, 1914 cited in Baldwin, 1986:116). Here Mead shows how we are able to “evaluate the innovations of the “I” from the perspective of society, encouraging socially common innovations, while discouraging undesirable actions” (Baldwin, 1986:116).

This is related to the issue of self-objectification in which young girls emphasise their physical body as seen by others and de-emphasise their own perception of the self (Rush, 2006: 43).

Adapting Mead‟s theory, the component of the “I” for young girls and their subjective belief of themselves is the innocent child who does not need to worry about physical appearance. However, the “Me” component, while giving the objective perspective, is enhanced by the production of sexualised images. Young girls are influenced to believe that this sexualised image is a ubiquitous look for other girls and as the others begin to dress and act in sexually mature ways, it becomes perceived as the norm. Young girls would be happy with any toy or clothing that is bought for them, however, the “me” recognises what is regarded as socially desirable and undesirable. Yet unfortunately, in today’s modern society what is desired is sexual appeal, an asset we are encouraged to learn and reproduce.

Conclusion

To conclude my journal I want to pose a question which I feel is central to this issue. Why is it that sexual appeal has become considered as an important value in today’s society? Not only have the media created depictions of women which are constructed as “sexy” and “seductive”, but in some cases they are presented as role models to young girls. I have shown through some of the examples that various products, including everyday clothing, are becoming more and more adult-like encouraging girls to present themselves in a way we might expect a twenty-year-old woman to dress. I think that through the acknowledgement of many of the issues that were raised throughout, clearly the answer is that profit serves as the main drive for these companies and institutions who work on the basis that sex sells. They do not comprehend the damage they are doing to many young girls, as these children begin to trust what they see as the look which they too should be following.

In so many ways young girls are growing up in a shadow cast by a sexualised vision of themselves and others, dressed head to toe in clothing intended for adults, with a mindset based on image and sexual appeal. However, I believe that childhood is a period in every human being’s life which should be preserved and enjoyed as a child, not under the false constructions of the media. It is a time in your life which needs to be enjoyed for being who you are, having fun and not worrying what everyone else thinks. I hope that my cousin will be able to realise that she does not need to abide by a certain code to “fit in” or dress in a certain way to be noticed. Beauty is an accolade which comes from within and this is a message which all young girls across the world, including my cousin, should learn to accept.

Bibliography

AyoTechnologyOfficial (2010) 50 Cent ft. Justin Timberlake- Ayo Technology. [Online] Available at: < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=olCQI7Npx2I&feature=fvst> [Accessed 1 March 2012].

Baldwin D.J. (1986) George Herbert Mead: The Unifying Theory for Sociology. London: Sage Publications.

Brooks, K. (2008) Consuming Innocence: Popular Culture and Our Children. [E-book] Queensland: University of Queensland Press. Available through: <http://www.books.google.co.uk/books> [Accessed 15 February 2012].

Daily Mail Reporter (2011) Fury as Matalan Sells Padded Bras to Eight Year Old Girls. Mail Online, [Online] 14 March. Available at: <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1366012/Fury- Matalan-sells-padded-bras-pre-teen-girls.html> [Accessed 23 February 2012].

Dant, T. (2003) Critical Social Theory: Culture, Society and Critique. London: Sage Publications.

Durham, G.M. (2009) The Lolita Effect. London: Duckworth Overlook.

Edwards, T. (2011) Fashion In Focus: Concepts, Practises and Politics. [E-book] Oxon: Routledge. Available through: <http://www.books.google.co.uk/books> [Accessed 15 February 2012].

Hamilton, M. (2008) The Seduction of Girls: The Human Cost. In: Reist, T.M. 2008. Getting Real: Challenging the Sexualisation of Girls. Australia: Spinifex Press, pp.55-64.

Harrison, A. (2011) Music Videos Need Age Rating Says Review. BBC News, [Online] 3 June. Available at: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-13639487> [Accessed 23 February 2012].

In-Debate. (2011) Are We Sexualising Children Too Early? [Online] Available at: <http://www.in- debate.com/2011/10/sexualising-children> [Accessed 20 February 2012].

Inglis, F. (1990) Media Theory: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Lemert, C and A, Branaman. (1997) The Goffman Reader. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

MacRae, F and N, Sears. (2007) The Little Girls „Sexualised‟ At The Age Of Five. Mail Online, [Online] 20 February. Available at: <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-437343/The-little- girls-sexualised-age-five.html> [Accessed 23 February 2012].

Marcuse, H. (1964) One- Dimensional Man. London: Routledge.

Metrolyrics, n.d. Ayo Technology lyrics, 50 Cent. [Online] Available at: <http://www.metrolyrics.com/ayo-technology-lyrics-50-cent.html > [Accessed 1 March 2012].

Mills, C.W. (1959) The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: University Press.

Poulter, S. (2010) Beyonce Turns Up the Heat A Little Too Much As Racy Perfume Is Banned From Daytime TV. Mail Online, [Online] 17 November. Available at: <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-1330408/Beyonce-perfume-advert-sexy-banned- daytime-TV.html> [Accessed 23 February 2012].

Rauton, D and P, Watson. (2005) Music Videos. In: Paasonen, S., Nikunen, K, and Saarenmaa, L., 2007. Pornification: Sex and Sexuality in Media Culture. Oxford: Berg Publishers, pp.115.

Reist, T.M. (2008) Getting Real: Challenging the Sexualisation of Girls. Australia: Spinifex Press.

River Island (2012) River Island Girls. [Online] Available at: <http://www.riverisland.com/online/girls> [Accessed 27 February 2012].

Rossi, M.J. (2005) Outdoor Pornification: Advertising Heterosexuality in the Street. In: Paasonen, S., Nikunen, K, and Saarenmaa, L., 2007. Pornification: Sex and Sexuality in Media Culture. Oxford: Berg Publishers, pp.129.

Rush, E. (2006) What are the Risks of Premature Sexualisation for Children? In: Reist, T.M., 2008. Getting Real: Challenging the Sexualisation of Girls. Australia: Spinifex Press, pp.41-49.

Shipman, T. (2011) High Street Shops to Ban Padded Bras and „Sexually Suggestive‟ Clothes for Young Girls. Mail Online, [Online] 4 June. Available at: <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article- 1394123/High-street-shops-ban-clothes-sexualise-little-girls.html> [Accessed 23 February 2012].

Strasburger, C. V. and Wilson, J.B. (2002) Children, Adolescents and the Media. London: Sage Publications.

Strinati, D. (1995) An Introduction to Theories of Popular Culture. London: Routledge.

Strinati, D. (2004) An Introduction to Theories of Popular Culture. 2nd Ed. London: Routledge.

Walter, N. (2010) Living Dolls: The Return of Sexism. London: Virago Press.

Williams, R. (1980) Erving Goffman. In: R, Stones ed. 2008. Key Sociological Thinkers. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wright, E.J. (2011) The Sexualisation of America’s Kids and How to Stop It. [E-book] Bloomington: Iuniverse. Available through :< http://books.google.co.uk/books> [Accessed 15 February 2012].

Electronic Images

Front cover: Unswbmedia (2010) Is Barbie Really A Bitch? [Image online] Available at: <http://www.unswbmedia.org/mdia1001/?page_id=8&paged=105> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Image 1: Eurweb (2011) Beyonce’s Heat Is UK’s Top Selling Celebrity Scent, Mariah No.4. [Image online] Available at: <http://www.eurweb.com/2011/08/beyonce%E2%80%99s-heat-is- uk%E2%80%99s-top-selling-celebrity-scent-mariah-no-4/> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Image 2: MTV Style (2011) Rosie Huntingdon-Whiteley Basically Naked In Burberry Ads. [Image online] Available at: <http://style.mtv.com/2011/07/13/rosie-huntington-whiteley-burberry- body/> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Image 3: River Island Girls (2012) Girls Pink Leopard Skinny Jeans. [Image online] Available at: <http://www.riverisland.com/Online/girls/jeans/girls-pink-leopard-print-skinny-jeans-801718> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Image 4: River Island Girls (2012) Girls Cream Ra-Ra Skirt. [Image online] Available at: <http://www.riverisland.com/Online/girls/skirts–shorts/girls-cream-lace-ra-ra-skirt-801681> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Image 5: Matalan (2010) Heart Bra Peach. [Image online] Available at: <http://www.matalan.co.uk/fcp/product/fashion-to-buy-online-underwear-&-socks/heart-bra- peach> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Image 6: Mail Onlinen (2011) High Street Shops to Ban Padded Bras and ‘Sexually Suggestive’

Clothes for Young Girls. [Image online] Available at: <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article- 1394123/High-street-shops-ban-clothes-sexualise-little-girls.html> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Image 7: The Guardian (2011) Bratz Case Resolved With $88.4m Payout By Mattel. [Image online] Available at: < http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/apr/22/bratz-dolls-case-resolved-payout> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Image 8: Cartoon Pictures (2012) Classic Barbie. [Image online] Available at: <http://www.cartoonpictures5.com/barbie-doll-pictures.2012> [Accessed 13 March 2012].

.